Tom Chantrell and the World of British Film Posters

by Sim Branaghan

What links the films

Brighton Rock,

Summer Holiday,

One Million Years BC,

Gonks Go Beat,

East of Eden,

Carry On Screaming,

Bonnie and Clyde,

Let's Make Love,

Star Wars,

Housewives On the Job,

Far From the Madding Crowd and

Hellcat Mud Wrestlers? I'll give you a clue, it isn't Thomas Hardy. In fact it is the unassuming Manchester artist Tom Chantrell, who painted these and many hundreds of other classic film posters in a stunning career that spanned half a century, and took in what most would consider the great post-war Golden Age of popular cinema.

1. Prologue: The Birth of British Cinema

To properly understand Tom’s career, we first need to appreciate his position in the historical development of UK cinema-advertising, and why he arrived at such a critical point in its development. The story of British cinema itself starts very quietly in February 1896, with a couple of London scientific-club demonstrations of the latest engineering breakthrough - moving-image film projectors. The remarkable success of these events led to the machines being quickly adopted as a popular novelty attraction by the Music Halls of the day, and the first fifteen years or so of British cinema underline its early status as just another gimmick on Variety Bills, sharing stage-space with comedians, singers, magicians and conjurors, trapeze artists, acrobats, and any number of oddball attractions. Films were randomly screened wherever space could be found, not only in theatres, but also rented Public Halls, fairground tents, and even hastily-converted empty shops. The posters advertising these events inevitably tended to follow the conventional Music Hall template - a tall, thin, text-only "letterpress" bill, featuring a simple descending list of attractions on offer, naturally including a selection of the latest increasingly popular "Cinematograph" short films.

Things began to change around 1910. The films themselves were becoming longer and more sophisticated, now capable of being sold and advertised individually, often by promotion of their actors as newly-emerging "film stars". With Music Hall and Variety on the wane, purpose-built cinemas began to be constructed, now dedicated to film-shows alone, and new companies were established specifically to run chains of these cinemas, and distribute exclusively-licenced packages of films to them. All of these combined factors meant that film posters themselves changed and became more ambitious, with an emerging style now echoing the traditional British theatre poster, featuring a full-colour artistic depiction of a single dramatic or comical scene. These were in a large vertical format of about 40"x30", and printed via the craftsman-based technique of "hand-drawn litho", in which original watercolour designs were laboriously hand-copied onto the actual printing-plates by artisans at the printing works. It was a meticulous, painstaking business, but resulted in gloriously colourful eye-catching posters that had audiences queuing up outside their local 'fleapit' to catch the latest epic advertised. Sometimes cheaper posters would be produced by the alternate method of "silkscreen" printing, basically a stencil process that resulted in much simpler images, but was perfectly adequate for the more minor attractions on offer.

2. Context: The Rise of Illustrated Film Posters

As the 1920s progressed Hollywood came to the fore, and the great Studios like Warner Brothers, 20th-Century Fox, MGM etc began to dominate the international marketplace, exporting thousands of US-printed posters all over the world to advertise their films, which were now gaining a stranglehold on the British market in particular. To try and support struggling British producers, the government introduced a protectionist measure - the so-called "Quota Act" of 1927 - which forced UK cinemas to begin showing a fixed minimum quota of British films in their programmes. This gave a huge boost to our film business, and forced Hollywood to adjust its strategies - the US studios reluctantly began to set up UK production-subsidiaries, and simultaneously contracted British advertising-agencies to design and produce their UK publicity. For example, Fox and Warners jointly retained the London agency Allardyce Palmer in 1936 to handle their advertising for them.

There was one final breakthrough at this point, which (although it didn't make much impact at the time) was to have critical long-term significance. As we've already noted, between about 1910 - 1935 most British film posters were printed in a portrait style of roughly 40"x30", based on the traditional Victorian theatre-poster layout. This was also conveniently similar to the established American movie-poster format of 41"x27" - the so-called "One-Sheet" - which meant that US posters could either be imported here direct, or at the very least have their designs adapted with minimal alteration onto British-printed posters. However, in 1936 one UK distributor - the Gaumont-British company - introduced a radical new poster-format: the LANDSCAPE 30"x40" "Quad Crown" style. These were an immediate hit with the public, and GB's rival distributors quickly adopted the format themselves, making it the default style by the end of the decade. This suddenly meant most US designs could no longer easily be adapted from one shape to another, and the possibility of designing entirely new and different artwork for imported films became an option. For any young and ambitious British illustrator, particularly one with showbiz in his blood and an instinctive grasp of how to sell films to a mass-audience, this was the opportunity of a lifetime. Step forward Tom Chantrell.

3. Family and Childhood

Thomas William Chantrell was born in Ardwick, Manchester on 20th December 1916, the ninth and last child of James and Emily, who had already raised eight earlier daughters over the previous eighteen years of their marriage. Father James was a Music Hall performer who had toured the world in a trapeze-act called "

The Fabulous Chantrells" (claiming to have done the Triple), and was also in casual partnership with a Black musician named Lewis who had earlier bought his freedom from the American Deep South - the pair apparently delighted in making a racket playing Jazz together to the early hours. According to his Birth Certificate, at the time of Tom's arrival the 64-year-old James's occupation was "Picture House Assistant".

Growing up in a family of girls, Tom was always going to go his own way, and very early on showed a natural talent for art. In fact, he always liked to claim that his first piece of Commercial Illustration was produced aged five, when his schoolteacher asked the class to paint a picture of 'Tom' from Kingsley's The Water Babies, and apparently liked the young Chantrell's contribution so much she paid him a penny for it, and pinned it up on the classroom wall. He later received a lot of encouragement from his Art Teacher, and at age thirteen won a prestigious national competition to design a disarmament poster for the League of Nations. Leaving his Grammar School at fifteen he very briefly attended Manchester Art College, but (in typically pragmatic style) quickly decided this was a complete waste of time, as his talents were already sufficiently well-developed for him to earn a living from them. He therefore took some samples of his best work into Rydales, a local advertising agency, and was immediately told to start there the following Monday.

After a few months at Rydales, the firm's resident top illustrator left to form his own company, and took a handful of the best artists with him, including Tom. For a year or so everything went well, but the teenage Chantrell was still impetuous and hot-headed enough to allow his temper to get him into trouble. One day there was an argument in the studio concerning an unsatisfactory piece of work, wrongly blamed on Tom. A shouting-match quickly escalated into a full-blown punch-up with his Studio Manager, as paint-pots flew and easels crashed around them. Inevitably sacked on the spot, Tom felt he had seen enough of Manchester, and fancied trying his luck down South. In 1933, aged seventeen, he moved to London, at first lodging with his sister Phyllis in leafy Hampstead.

4. Arrival in London

He quickly talked his way into a job with a silkscreen printer, carefully omitting to inform his new boss he was completely ignorant of the process. His first attempt was such an outright disaster he had no option but to admit the truth, and the Chantrell charm must have done its work, because the manager was sufficiently won-over to keep him on and train him up personally. After a couple of years of this (the early experience in designing effectively eye-catching silkscreens would prove invaluable later in his career), he moved to another Studio, Bateman Artists, on Carmelite Street EC4, just above Blackfriars Bridge in the City.

Bateman Artists was a small studio of about eight designers and illustrators, established ten years earlier by Bill Bateman, an amiable and rather cultivated boss who apparently had little in common with the brash advertising men who routinely supplied him with work. Bateman's main client was in fact ad-agency Allardyce Palmer Ltd, who shared the same building. Most of the creative-work Allardyce thus fed to Bateman was for technical and engineeering accounts: British Aluminium, Smith's Industrial Instruments, Percival Provost aircraft, Westminster Dredgers etc. But two new accounts that arrived more or less simultaneously with Tom himself were the major US film distributors Warner Brothers and 20th Century-Fox .....though these were quietly looked down on as a "necessary evil" by the agency itself, and seen as the "rubbishy, lower end" of the advertising market. The required film posters for Warners and Fox were initially mostly designed by Bateman's senior illustrator WH Pinyon, and the young Chantrell generally found himself working on the less glamorous but more respectable engineering and industrial accounts, drawing boats, planes and buses etc.

Then in October 1938 the flagship "Warner West End" cinema opened in Leicester Square, with Errol Flynn's classic Adventures of Robin Hood. A few weeks later Robin was replaced by the slightly less classic crime-comedy The Amazing Dr Clitterhouse starring Edward G. Robinson, and Tom was given the job of designing a large six-sheet poster for display outside the cinema. It was a taste of things to come, and other similar jobs were clearly on the horizon, when War suddenly intervened.

5. Wartime Adventures

Called up in 1940, Tom registered as a Conscientious Objector, and opted for the Royal Engineers and a career in bomb-disposal. By this point he had married his girlfriend Alice, and the resulting posting to barracks in Tunbridge Wells seemed to offer the young couple the best chance of spending time together. Exactly how much time this might amount to remained uncertain, as the average life-expectancy of a squaddie working on UXBs was then about ten days, but Tom nevertheless spent several years digging mines out of beaches along the Kent and Sussex coast. This hair-raising period of his life also gave him an enduring contempt for authority in all its forms. Later colleague Ray Youngs recalls that one of Tom's most difficult jobs concerned a flying bomb that had gone down just outside Leysdown on the Isle of Sheppey. Since Sheppey is mostly made up of marshes and tidal mud, the bomb had gone in very deep at an extremely awkward angle, and the team spent several anxious days carefully digging it out and removing the lethal fuses. The officer theoretically in charge of the squad was not present for this (being on leave visiting his heavily-pregnant wife), but nevertheless was later personally decorated in recognition of the successful operation. For ever afterwards Tom always maintained that OBE actually stood for Other Buggers' Efforts.

Tom spent the final year or so of the conflict in a Division producing signs and propaganda posters for the War effort, after another officer had spotted his artistic ability and got him specially transferred to a place where better use could be made of his talents. Eventually he was demobbed in 1946, and the 'returnees' policy of the time meant he went straight back to Bateman Artists, by now relocated to offices in Corner Buildings, 109 Kingsway WC2 in Holborn.

6. Back to Work

Pinyon was still handling most of the film posters, but from this point Tom's involvement steadily increased. One of the first quads he recalled painting after the War was Forever Amber (1947) with Linda Darnell, and another famous title of the same year was Brighton Rock, with a vivid portrait of baby-faced gangster Richard Attenborough. Warner Brothers were by now closely linked with major UK distributor Associated British-Pathe, so many of the poster-assignments arriving at on Tom's desk were now from this home-grown company as well. In 1950 Allardyce Palmer bought up Bateman Artists outright as a fully-owned creative wing, Bill Bateman retiring and overall control passing to agency boss Peter Palmer. A new recruit to the Studio had arrived the previous year: the seventeen-year-old Tom Beauvais (whose father Arnold had also been a poster-artist himself before the War), and the younger Tom became the first in a long line of assistants to Chantrell, eventually going on to design and illustrate many of his own posters.

With the film-work continuing to grow, and rumoured distributor-mergers on the horizon indicating the trend was only going to increase, the decision was taken in 1957 to set up a new "Entertainments Publicity Division" in Screen House, 119-125 Wardour Street, at the very heart of London's film business district in cosmopolitan Soho. This was jointly headed up by Art Director Chantrell, and Account Executive Stan Heudebourck who had first joined Allardyce in 1950 and became the main point of contact with the clients, liaising with the Publicity Managers (respectively Al Shute of Warners, and John Fairbairn of Fox) and taking artwork around for approval etc. The relationship was fairly congenial, though the two men didn't always get along perfectly - Heudebourck (who at the time had Anglicised his surname to 'Burke' - fittingly, as Tom felt) liked things to run as efficiently as possible, which tended to clash with Tom's more laid-back approach. Tom Beauvais remembers one argument ending with Chantrell exploding "Why does everything have to be so BLOODY URGENT all the time?" - to which Stan could only patiently point out that this was the nature of the business they were in, like it or not. But there's no doubt that Tom generally preferred to work at his own pace - as Ray Youngs recalls, he liked to spend the day chatting and arguing politics, philosophy or psychology (anything that came to mind really), doing much of his actual painting at home late into the night, where he would work quietly with a glass of whisky in one hand, and some soothing classical music playing low in the background.

7. Film Publicity in the Fifties and Sixties

One key change that came about in British posters during the early 1950s was the switchover from hand-drawn to photo-litho printing. Attempts to employ litho for large-format photographic-reproduction had been going on experimentally for decades, but had always been thwarted by the unstable nature of the chemicals involved. However in 1950, new light-sensitive Diazonium Resin plate-coatings were introduced, that eliminated most of the earlier difficulties. By 1954 these were being used to print British film posters, a huge step forward in terms of the resulting look of the art. For the first time, ACCURATE PHOTOGRAPHIC REPRODUCTION of original painted artwork could be achieved, just at the point that Chantrell's career in this field was about to properly take off.

Tom's poster-work was inevitably driven and defined by whatever Warners and Fox were releasing at the time, so the mid-late 50s were dominated by prestige epics like

East of Eden (1955),

The King and I (1956),

Anastasia (1956),

Bus Stop (1956),

An Affair To Remember (1957),

South Pacific (1958) and so on, with Tom painting the great Hollywood stars of the era, like James Dean, Yul Brynner, John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Cary Grant, Robert Mitchum etc. But a major shift occurred in 1959 with the formation of Warner-Pathe distributors, a merger of Warner Brothers and Associated British-Pathe (the latter already being tied up with independent US studio Allied Artists). Pop began to arrive at this point, initially with Fox's Elvis series, starting with

Love Me Tender (1956), then shortly followed by their British imitations with Cliff, beginning with

The Young Ones (1961). As the years passed and the work built up, three new "Studio Boys" were taken on as apprentices - John Chapman in 1955, Ray Youngs in 1960, and Colin Leary in 1962, all of whom eventually, like Beauvais, progressed to working on their own posters for the agency.

As the 60s progressed the material passing through the agency became steadily more eclectic, particularly after 1962 when British indie distributor Anglo-Amalgamated joined the Warner-Pathe conglomerate. Anglo had been handling the films of celebrated US exploiteers American International Pictures (AIP) since the mid-50s, so Tom was kept busy repainting US designs for all sorts of teenage dragstrip / beach party / biker gang melodramas, plus the later Edgar Allan Poe adaptations such as

The Raven (1963) and

Masque of the Red Death (1964). Anglo also distributed the early

Carry Ons, and Tom painted the six classic titles

Cabby,

Jack,

Spying,

Cleo,

Cowboy and

Screaming. In 1967 Anglo made a brief and ill-fated attempt to move upmarket, shooting a sumptuous period version of Thomas Hardy's classic

Far From the Madding Crowd. When Warner-Pathe came to release this, they inevitably had absolutely no idea how to market it, so Tom just gave his poster a subtle cowboy twist, hoping it might catch on as a 'Wessex Western'!

8. Family Life

Tom's private life went through a major upheaval in the early 60s. He had already raised two children with Alice, Stephen and Sue, when in September 1962, out of boredom and a desire to try something different, he began attending art classes with Ray Youngs at St Martin's college. (Ray was actually in the Life drawing class: "When Chan saw my paintings of naked ladies he liked the look of this so came along to join, but as the life class was full he had to enrol in the still-life class instead, painting Greek busts and urns!") Nevertheless, it was a fateful decision - while there he met an eighteen-year-old Chinese student named Shirley How Har Lui, and the two gradually became friends and fell in love. They moved in together in 1965, and had twin daughters Jaqui and Louise in 1968, eventually marrying in 1974 after Tom's divorce had finally come through.

Shirley's arrival changed Tom's approach to his work. In the early part of his career he never felt anyone took much interest in his painting, and indeed didn't even consider himself a particularly good artist. On an early date with Shirley he casually pointed out a few of his posters pasted up around the Underground, explaining their distinctive "Chantrell" signatures were his. At first Shirley thought he was joking, and when Tom finally managed to convince her, was hugely impressed and excited at such exquisitely skillful and dramatic painting. With her enthusiastic support and encouragement Tom started to take himself more seriously as an artist, crucially beginning to save his artwork and proof copies of posters, while also becoming more confident about his own unique talents.

Perhaps Tom's most famous client of all arrived just as he was settling down with Shirley: Hammer Films. In 1965 Hammer switched distribution to Associated British, and their advertising accordingly moved to Allardyce. As a result, Tom went on to paint all of their posters between

The Nanny (1965) and

Taste the Blood of Dracula (1969), effectively becoming the company's 'House Artist' of the period, and nowadays inextricably linked in many fans' minds with their most celebrated imagery. Tom not only painted Hammer's iconic quads, he also produced large amounts of speculative pre-production artwork, which the company used to help try and sell the projects to the distributors, and thus raise the necessary cash to get them made in the first place. These fascinating images often bear little or no resemblance to the finished film, and in several cases failed to get made at all, imbuing the handful of surviving examples with a strange atmosphere of 'epics that never were'. Tom certainly enjoyed a friendly working relationship with Hammer's shrewd boss James Carreras, one of the all-time great salesmen of British cinema, who, like Tom, possessed an unerring instinct for what the public wanted.

9. Final Days at the Agency

By the end of the 60s Fox and Warners in America were involved in the emerging New Wave, producing ground-breaking cult successes like

Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and

Bullitt (1968), for which Tom designed posters often considerably superior to the nondescript US originals. But closer to home, things were not looking so good. In 1970 Allardyce Palmer was bought by advertising conglomerate KMP, and merged with another agency to make Allardyce Hampshire, Peter Palmer leaving to be replaced by Donald Bailey. The office shifted to 213 Oxford Street (above Littlewoods - a noisy open-plan layout, as opposed to Screen House's cosier "nest of rooms", which Tom had much preferred), and, even more disastrously, a new level of "visualisers" and other creative staff were brought in, whose generally hopeless input and advice increasingly grated on the stubborn Chantrell, who had long-since grown used to doing things his own way, without outside interference. A sharp insight into his frustration is provided by a letter he wrote in February 1972, in response to a complaint from one of the new Directors, who had noticed that Tom and Ray (then sharing a cramped office) were not always at their desks by 9am.

Tom opens by itemising his and Ray's joint output over the preceding two months - taking December 1971 alone, this comprises: "16½ days - 70 jobs. 8 quad poster layouts / 7 quad poster finished drawings / 7 quad poster revised finished drawings / 16 double crown poster layouts / 1 trade ad finished drawing / 7 trade ad layouts / 15 press ad layouts / 3 press ad finished drawings / 1 bus side poster layout / 1 location sketching job at Warner Brothers / 2 screenings / 3 meetings /+ various misc. jobs (displays etc)."

January 1972 is a similar list, and Tom then gives the thirty film titles involved, which include

French Connection,

Le Mans,

Clockwork Orange,

Klute,

Dirty Harry,

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid/Mash,

The Cowboys,

The Devils,

Crucible of Terror and

Horror Express: "I include the titles to show you that they were not lots of tries at the same job, but separate creative concepts". The remainder of the letter is a terse explanation of the way he and Ray were then working: "As you know, a quad poster comprises Finished Colour Artwork - usually multiple figures - and between fifty and one hundred words letraset (cheaper and quicker than photosetting) ...All these jobs met their almost impossible deadlines: we have had no complaints about timing, and as you know film ads have to be both right and on time - Mr Fairbairn doesn't expect me to have a weekend off, he 'Wants it Monday', and this goes for everyone else...

"...many jobs are given to us after 5.30pm. Ray is available lunchtime and between 5.30 and 7pm - sometimes later for the last minute briefs...we both regularly work till about three in the morning. I think our good performance over the last two months has been largely due to our temporary room, which though cramped, is quiet, and the natural light adequate - our previous room was noisy. Stan [Burke] said of it 'How in God's name can you work in here?' ...Ray and I make up any time necessary by under-booking overtime, and charging low rates for freelance. Yours sincerely, Tom."

It is fairly obvious in which direction his thoughts were heading by this point, and a few weeks later Tom finally handed in his notice, his career as a salaried Art Director at an end. He continued to work freelance for the agency (on a fixed fee of £230 for three layouts and a finished artwork), and painted several further notable Fox and Warners quads over the next two years. But in 1974 (undoubtedly weakened both by his departure, and the heavy-overcharging of their remaining clients), Allardyce suddenly lost both these historic film accounts to rival agencies within a few months of each other. They staggered on for a few more unhappy years, but the knockout blow came in 1977 with the collapse of their biggest-spending client Brentford Nylons, which left the hapless agency liable for their accumulated debts. The once celebrated and influential Allardyce was defunct and forgotten by the end of 1978.

10. Going Freelance

For Tom however, going freelance provided a new lease of life, and this final period of his poster-career, 1972-85, is in many ways the most intriguing, being packed with scores of offbeat quads for oddball films. As Tom told it, by the late 60s he couldn't walk down Wardour Street without being accosted by half a dozen passing producers desperate to commission a colourful Chantell poster for their latest epic, and his 25 post-war years at Allardyce had provided an enviable reputation as the country's best-known, most successful and experienced film poster artist. The move to freelance also neatly coincided with a dramatic shift in the overall shape of Britain's film business as a whole.

As audiences steadily declined, larger cinemas had increasing difficulty filling their cavernous auditoriums, and the obvious solution was to simply subdivide the space. Beginning in 1970, the big circuit-cinemas were "tripled" by converting their interiors into three separate screens, and - since most towns still had a competing ABC and Odeon on the High Street - this suddenly meant a potential choice of up to six different films. But how were cinemas going to programme so many screens, with Hollywood already cutting back dramatically on production? Part of the answer lay in a distinctly downmarket side-effect of the new ‘Permissive Society’ of the late-60s.

An increasingly liberal approach to censorship meant that the BBFC's classification-categories were revised in summer 1970, with a new intermediate "AA" certificate introduced for young teenagers, and the age-bar of the Adults Only "X" correspondingly raised from 16 to 18. This immediately opened the floodgates to a huge wave of 'Sexploitation' (both British and Continental) which titillated UK cinemagoers for a disgraceful fifteen years up to the mid-80s, and led to the establishment of about twenty new independent distributors over the 1970s to supply it, more than twice the number of any previous decade.

11. Independent Work in the Seventies

Virtually all these indies are now long gone and (sometimes gratefully) forgotten, but Tom worked for the lot at one time or another: New Realm, Miracle, Gala, Eagle, Tigon, Target, Scotia-Barber, Hemdale, Oppidan, Variety, ITC, Brent-Walker, Alpha, Enterprise, Cannon, Entertainment..... the list is endless. Though sex was always top of the menu, every other conceivable genre that might turn a few quid for its distributor made an appearance: kung fu, horror, kung fu-horror, cheap war, cheaper sci-fi, dubbed crime thrillers, full-length children's cartoons, witless teenage sex-comedies, full-length adult cartoons that WERE witless sex-comedies, Japanese Kaiju monster-mashes, Italian Giallo murder-mysteries, spaghetti westerns, French Arthouse, American Grindhouse, Turkish Bathhouse and Australian Madhouse, you name it, it got some kind of showing in British cinemas in the 1970s. And when you needed an appropriately gratuitous poster to pull in the punters, Tom Chantrell was your man. When it came to cleavage, Nobody Did It Better.

Tom received work from all directions in the 70s, but was principally supplied by three main agents: Alan Wheatley, Mike Wheeler, plus his old Allardyce-colleagues John Chapman and Tom Beauvais, who had joined forces in 1975 as independent design-studio Chapman-Beauvais (still working for Fox and Warners), and later employed Ray Youngs and Colin Leary to help out, keeping the old gang together. The sheer variety of assignments involved in the resulting hotch-potch of work is mind-boggling - Tom could (and did) go from threadbare British sex-comedies like

Come Play With Me to international blockbusters like

Star Wars, and back again, in the space of a few weeks. Based on his reputation for cinema-work, he also branched out into related fields, illustrating movie-soundtrack album-sleeves for the MFP (Music For Pleasure) label, and movie-themed book-jackets (on a series of popular genre-histories) for the publisher Hamlyn. There were also a few one-off commissioned portraits, including the well-known footballer Kevin Keegan, and a (slightly less well-known, but very rich) Greek shipping magnate.

The final market which appeared in the early 80s, obviously tailor-made for Tom's talents, was of course video-sleeves, and these increasingly filled the gap left by the now rapidly-declining demand for illustrated quads. Videos also tended to pay better - up to £800 each by the end of the decade, more than twice what he could expect to get for a poster - though the artwork (following the demands of the distributors) was now becoming steadily more airbrushed and photo-realist. His final sequence of such titles included vintage BFI-label classics like

Lady Hamilton and

The Four Feathers, with a restored print of the latter being selected for a charity Royal Gala Performance at the National Film Theatre in October 1991, followed by limited theatrical release. Tom's epic, sweeping artwork of Ralph Richardson and June Duprez was thus printed up as a quad for the very last time, and appeared in the West End almost exactly 53 years to the day since

The Amazing Dr Clitterhouse had first opened in Leicester Square.

12. Retirement and the End of Painted Posters

What happened to kill off painted film posters? In a nutshell, the money ran out. At the end of the War in 1946, an incredible 1,635 million people visited the cinema in Britain - per capita, almost one visit a week for every person in the country. By 1984 this had fallen to just 54 million, a drop of 95%, with the per-capita average now less than one visit a year. Similarly, the number of operational cinemas over the same period had fallen from 4,720 to just 660, with only one out of every seven surviving. By 1985 all but a handful of the 70s indie distributors had gone, either switching over to video or withdrawing altogether, and the gig appeared to be well and truly up. The bottom had completely fallen out of the market, and artist-designed and illustrated posters were suddenly an expensive luxury a cash-strapped film business could no longer afford.

The cinema itself was of course saved by the arrival of the multiplex (and consequent revival of the vital teenage audience), but this development also coincided with the digital revolution, and the advent of cheap and flexible computer-based design programs like Photoshop. If traditional painted posters had perhaps hoped for a chance of riding back into fashion on the coat-tails of the multiplex boom, the AppleMac killed such dreams forever.

As for Tom, he accepted his enforced retirement amiably enough, and thereafter restricted his painting to the occasional family portrait and an annual valentine for Shirley. From the mid-90s he began to take an interest in the emerging film poster-collecting market, anonymously attending fairs and auctions, and socialising with the handful of fans that bothered to track him down. In the late-90s he became diabetic and was forced onto a blandly restrictive diet, which frustrated him as he loved good food. After suffering a minor heart-attack in early summer 2001 he grudgingly allowed himself to be admitted to the local hospital, and died there peacefully on 15th July, much mourned by everyone who knew him.

13. Evaluation and Epilogue

Questions about his overall output, and how much now survives, are tricky to pin down. Tom himself liked to quote a figure of 7,000 designs, but this would effectively have to include just about every idea he ever committed to paper, no matter how minor. A more realistic figure in terms of finished art would perhaps be between 6 - 800, though not all of these were eventually printed. As for individual posters, the size of the print-runs could also vary dramatically, depending on the film in question and the scale of its release. Blockbusters like

The Sound of Music or

Star Wars would have had initial quad runs of 10,000 or more, and additionally gone through several reprints to add details of Oscar-awards etc. In contrast, a tiny London-only release for an obscure imported horror like

Possession (1982) would have had a silkscreened run of, at most, perhaps 2 - 300, and the majority of these would have been pasted up and lost.

How would Tom have wanted to be remembered? Apart, naturally, from his magnificent art, I think it would probably be for his humour - he possessed an irresistibly dry Mancunian wit, and was a born raconteur. He enjoyed playing with words, and the copylines on dozens of his quads bear witness to a shameless delight in appallingly bad puns. If he couldn't inflict these on the posters themselves, he simply renamed the films he was working on:

Demetrius and the Gladiators became

Dermatitis and the Radiators,

When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth became

When Diana Dors Ruled the Earth, and

When the Legends Die became

When the Leg Ends Die! He was also endearingly human - he had a small swallow tattoo on his bicep, done when he was drunk once, which he immediately regretted but never bothered having removed, and his favourite term for a good layout was a growled "Real Ripsnorter"! As a friend he was loyal, generous, funny, and unfailingly good company.

Perhaps we should let him have the final word himself, so here is Tom's own account of the creation of one of his most famous posters, the unforgettable self-portrait that is

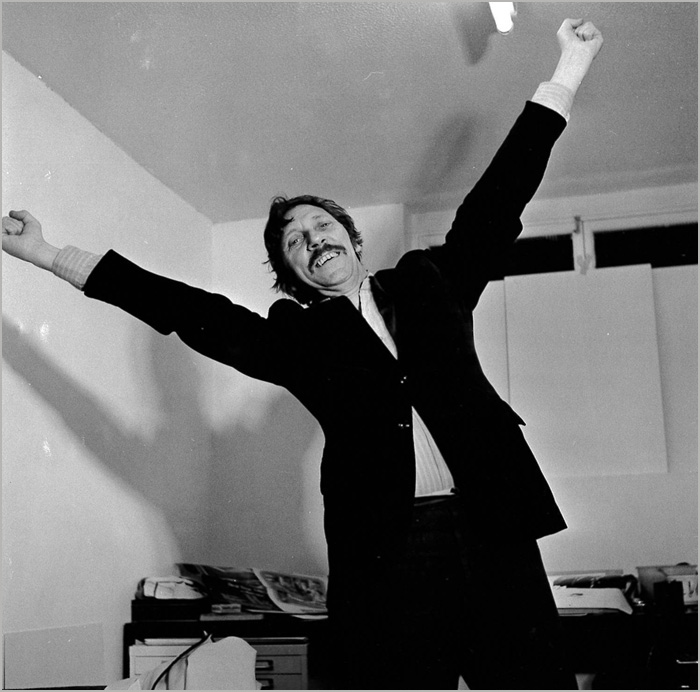

Dracula Has Risen From the Grave (1968):

"With only a title to go on, I painted a poster with a head of Count Dracula, snarling away with extended teeth, surmounting a montage of characters warding off vampires with a cross, a lady vampire drooling over another, and a female victim with a decolletage having her neck bitten. I used models as there were no stills provided, and later photographed a colleague with suitable under-chin lighting, then similarly posed while he took photographs of me. Denis was too benevolent-looking, so I used one of the photographs of myself to paint from, and added a busted grave to the montage.

Later some stills arrived, and it was possible to start on a third version. This poster had the neck-biting scene with Christopher Lee, and retained the open grave and malevolent self-portrait of Tom Chantrell. Then the distributor Warner Pathe said the film was going on in two weeks, and they wanted a poster right away. No still of Christopher Lee was available, so (what the heck!) the design was printed as it was. Nobody ever questioned the poster. They all think it's Christopher Lee, but it isn't, it's nasty ole' Count Chantrell!"

I hope that this website will encourage future generations of fans to discover and enjoy for themselves the fantastic artwork of nasty ole' Count Chantrell.

Sim Branaghan, November 2011

Sim Branaghan, November 2011.